A bit of fun mathematics here. On a cross-country train journey recently, I saw this post from @abakcus on X (formerly Twitter),

Be careful if you do the above calculation yourself. The result has 17 digits and so we’re hitting the limit of what a double precision 64-bit floating point number can represent. This means you may get some error in the calculation in the least significant digits depending on which language you use. Python uses Bignum arithmetic and so we don’t have to worry about precision issues when multiplying integers in Python. To do the calculation in R I used the Ryacas package, which allows me to do infinite precision calculations. The R code snippet below shows how,

library(Ryacas)

yac_str("111111111^2")which gives us the output below.

"12345678987654321"

The result of the multiplication, with its palindromic structure, is intriguing. But then you remember that we also have,

11 x 11 = 121

This made me wonder if there was a general pattern here. So I tried a few multiplications and got,

1 x 1 = 1

11 x 11 = 121

111 x 111 = 12321

1111 x 1111 = 1234321

11111 x 11111 = 123454321

111111 x 111111 = 12345654321

1111111 x 1111111 = 1234567654321

11111111 x 11111111 = 123456787654321

111111111 x 111111111 = 12345678987654321

Pretty interesting and I wondered why I had never spotted or been shown this pattern before.

On the return train journey a few days later I decided to occupy a bit of the time by looking for an explanation. With hindsight, the explanation was obvious (as is anything in hindsight), and I’m sure many other people have worked this out before. So my apologies if what I’m about to explain seems trivial, but for me this was something I hadn’t spotted before nor encountered before.

The first question that sprang to mind is, does it generalize to other bases? That is, in base n do we always get a pattern,

1n x 1n = 1n

11n x 11n = 121n

111n x 111n = 12321n

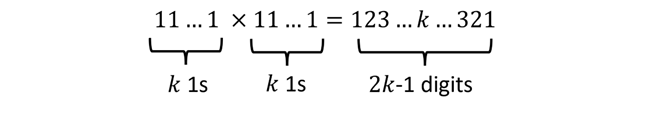

and so on. Obviously, there is a limitation here. In base n, the highest digit we can see in any position is n-1. So a more precise statement of the question is: for any base n and for any integer k < n, do we always have,

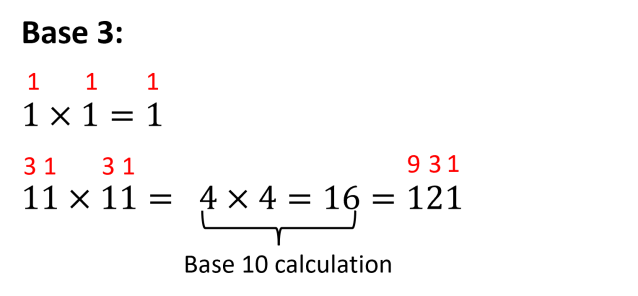

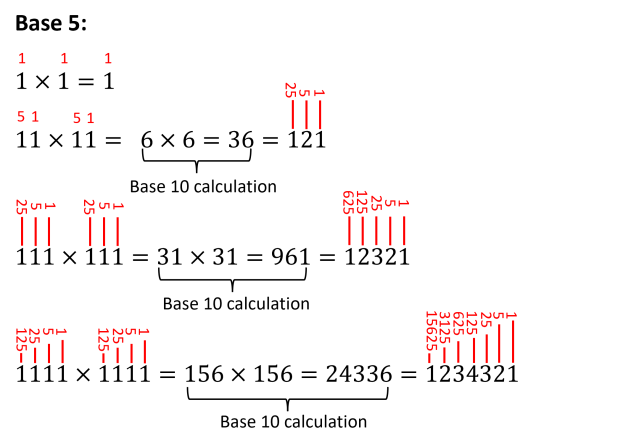

Let’s try it out. Remember for each base n we will have n-1 examples. The base 2 case (see below) is trivial, but it is still worth explicitly stating to highlight the pattern.

The red numbers denote the place-value corresponding to each digit position. The base 3 case gives two examples (see below),

Again, red numbers indicate place-values. We have also converted to a base 10 calculation in the middle to help work out what the final result on the far right-hand side should be.

The base 4 case gives three examples (see below). Now the annotation with the red numbers is getting a bit crowded, so we have rotated some of them to fit them all in. We have also connected the red numbers with lines to their corresponding digit to make the connection clearer.

The base 5 case gives four examples (see below),

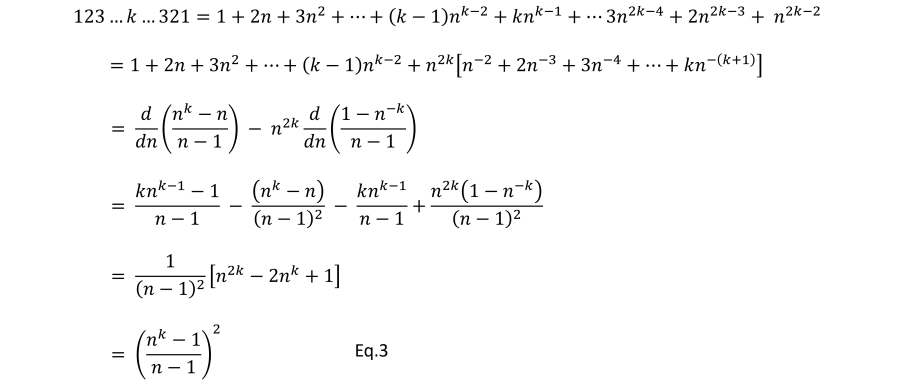

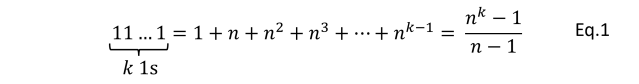

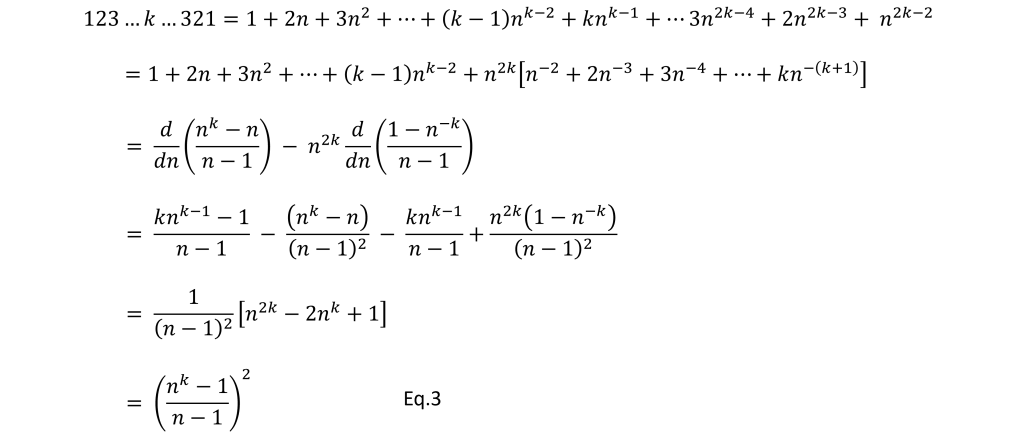

Ok, so there does appear to be a pattern emerging. Can we prove the general case? Let’s do the equivalent to what we have done above, i.e. convert the calculations from a place-value representation to a numeral. The base n number consisting of k 1s is,

Meaning that when we square the base n number that consists of k 1s, we get,

Similarly, we can write the base n number 1234…k….4321 as,

The final line in Eq.3 is the same as Eq.2, so yes, we have proved the pattern holds for any base n and for any k < n.

However, the above calculation feels a bit disappointing. By converting from the original place-value representation we hide what is really going on. Is there a way we can prove the result just using the place-value representations?

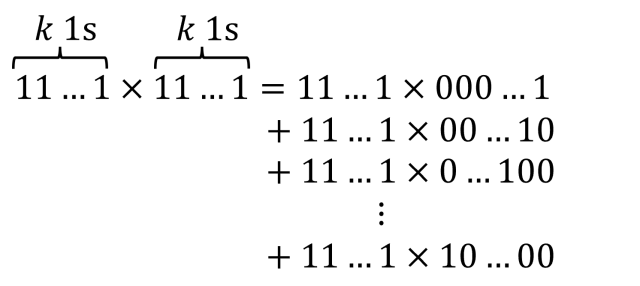

Remember we can break down any multiplication a x b as the sum of separate multiplications, each of which involves just one of the digits of b multiplying a. So we can write 11…1 x 11…1 as,

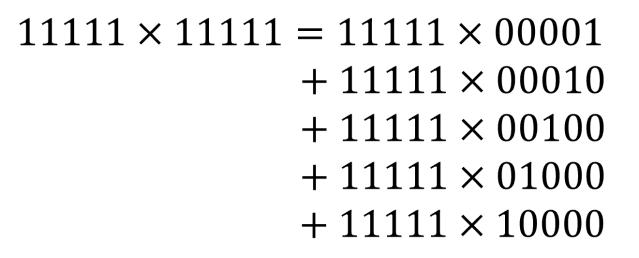

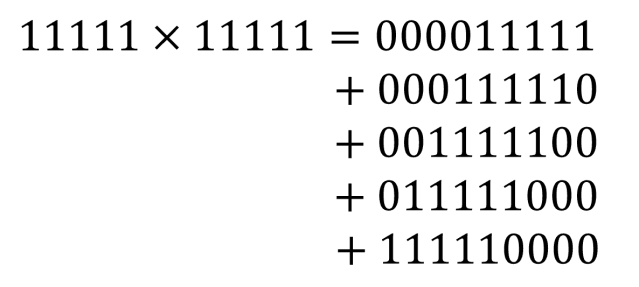

We can make the idea more concrete by looking at a specific example. Take the five digit number 11111. We can write the multiplication of 11111 by itself in the following way,

Note we haven’t said what base we’re in. That is because the decomposition above holds for any base. Now remember that when we multiply by a number of the form 00010, we shift the digits of whatever number we’re multiplying one place to the left. So, 11111 x 00010 = 111110. Likewise, when we multiply with 00100, we shift all digits two places to the left. If we multiply with 01000, we shift three digits to the left.

Now, with all that shifting of digits to the left we’re going to need a bigger register to align all of our multiplications. We’ll add zeros at the front of each multiplication. For example, 11111 x 00100 = 1111100 now becomes 11111 x 00100 = 001111100. With the extra zeros in place, we can finally write 11111 x 11111 as,

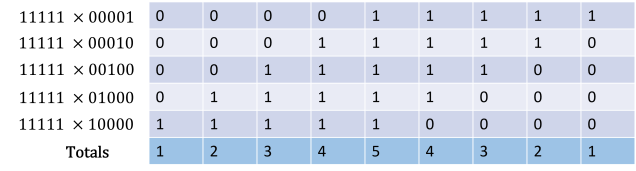

You can now see how all the 1s on the right-hand side line up in columns, allowing us to count how many we’ve got. Now we must impose the restriction that we are in base n > 5 so that when we add up all the 1s in a column we don’t get any carry over. If we put the above result in a table format, the column totals become clearer – see below.

Now it becomes clearer why we get the result 11111 x 11111 = 123454321 for any base n > 5. It is due to the shifting and aligning of multiple copies of the original starting number 11111.

The generalization to any number of 1s in the number we are squaring is obvious. This means we can also extend the palindromic pattern beyond base 10, for example to hexadecimal and multiply the hexadecimal number 11111111111111116 by itself to get,

11111111111111116 x 11111111111111116 = 123456789ABCDEFEDCBA987654321

Which means we get a pleasing palindrome that includes the alphabetic hexadecimal digits A,B,C,E,F. Try it in Python using the codeline below,

hex(0x111111111111111 * 0x111111111111111)You should get the output ‘0x123456789abcdefedcba987654321’

© 2023 David Hoyle. All Rights Reserved