TL;DR: Poor mathematical-based design and testing of models can lead to significant problems in production. Finding suitable ground truth data for testing of models can be difficult. Yet, many Data Science models make it into production without appropriate testing. In these circumstances testing with simulated data can be hugely valuable. In this post I explain why and how. In fact, I argue that testing with Data Science models should be non-negotiable.

Introduction

Imagine a scenario. You’re the manager of a Premier League soccer team. You wouldn’t sign a new striker without testing if they could actually kick a ball. Wouldn’t you?

In the bad old days before VAR it was not uncommon for a big centre-back to openly punch a striker in the face if the referee and assistant referees weren’t looking. Even today, just look at any top-flight soccer match and you’ll see the blatant holding and shirt-pulling that goes on. Real-world soccer matches are dirty. A successful striker has to deal with all these realities of the game, whilst also being able to kick the ball in the net. At the very least when signing a new striker you’d want to test whether they could score under ideal benign conditions. Wouldn’t you? You’d put the ball on the penalty spot, with an open goal, and see if your new striker could score. Wouldn’t you? Passing this test, wouldn’t tell you that your striker will perform well in a real game, but if they fail this “ideal conditions” test it will tell you that they won’t perform well in real circumstances. I call this the “Harry Redknapp test” – some readers will understand the reference1. If you don’t then read the footnote for an explanation.

How is this relevant to Data Science? One of the things I routinely do when implementing an algorithm is to test that implementation on simulated data. However, a common reaction I get from other Data Scientists is, “oh I don’t test on simulated data, it’s not real data. It’s not useful. It doesn’t tell you anything.” Oh yes it does! It tells you whether the algorithm you’ve implemented is accurate under the ideal conditions it was designed for. If your implementation performs badly on simulated data, you have a big problem! Your algorithm or your implementation of it has failed the “Harry Redknapp test”.

“Yeah, but I will have some ground-truth data I can test my implementation on instead, so I don’t need simulated data.” Not always. Are you 100% sure that that ground-truth data is correct? And what if you’re working on an unsupervised problem.

“Ok, but the chances of an algorithm implemented by experienced Data Scientists making it into production untested and with really bad performance characteristics is small”. Really!? I know of at least one implemented algorithm in production at a large organization that is actually an inconsistent estimator. An inconsistent estimator is one of the biggest sins an algorithm can commit. It means that even as we give the algorithm more and more ideal training data, it doesn’t produce the correct answer. It fails the “Harry Redknapp test”. I won’t name the organization in order to protect the guilty. I’ll explain more about inconsistent estimators later on.

So maybe I convinced you that simulated data can be useful. But what can it give you, what can’t it give you, and how do you go about it?”

What simulation will give you and what it won’t

To begin, we need to highlight some general but very important points about using simulated data:

- Because we want to want to generate data, we need a model of the data generation process, i.e. we need a generative model2.

- Because we want to mimic the stochastic nature of real data, our generative model of the data will be a probabilistic one.

- Because we are generating data from a model, what we can test are algorithms and processes that use that data, e.g. a parameter estimation process. We cannot test the model itself. Our conclusions are conditional on the model form being appropriate.

With those general points emphasized, let’s look in detail what we can get testing with simulated data.

What simulated data will give you

We can get a great deal from simulated data. As we said above, what we get is insight into the performance of algorithms that process the data, such as the parameter estimation process. Specifically, we can check whether our parameter estimation algorithm is, under ideal conditions,

- Consistent

- Biased

- Efficient

- Robust

I’ll explain each of these in detail below. We can also get insight into how fast our parameter estimation process runs or how much storage it requires. Running tests using simulated data can be extremely useful.

Consistency check

As a Data Scientist you’ll be familiar with the idea that if we have only a small amount of training data our parameter estimates for our trained model will not be accurate. However, if we have a lot of training data that matches the assumptions on which our parameter estimation algorithm is based, then we expect the trained parameter estimates to be close to their true values, i.e. close to the values which generated the data. As we increase the amount of training data, we expect our parameters estimates to get more and more accurate, converging ultimately to the true values in the limit of an infinite amount of training data. This is consistency.

In statistics, a formula or algorithm for estimating the parameters of a model is called an estimator. There can be multiple different estimators for the same model, some better than others. A consistent estimator is one whose expected value converges to the true value in the limit of an infinite amount of training data. An inconsistent estimator is one whose expected value doesn’t converge to the true value in the limit of an infinite amount of training data. Think about that for a moment,

An inconsistent estimator is an algorithm that doesn’t get better even when we give it a load more training data.

That is a bad algorithm! That is why I say constructing an inconsistent estimator is one of the worst sins a Data Scientist can commit. Very occasionally (rarely), an inconsistent estimator is constructed because it has other useful properties. But in general, it you encounter an inconsistent estimator you should take it as a sign of incompetence on the part of the Data Scientist who constructed it.

“Okay, okay, I get it. Inconsistent estimators are bad. But I don’t have an infinite amount of training data, so how can I actually check if my algorithm produces a consistent estimator? Surely, it can’t be done?” Yes, it can be done. What we’re looking for is convergence, i.e. parameter estimates getting closer and closer to the true values as we increase the training set size. I’ll give a demonstration of this in the next section when I show how to set up some simulation tests.

Bias check

Along with the concept of consistency comes the concept of bias. We said that a consistent estimator was one whose expectation value converges to the true value in the limit of an infinite amount of training data. However, that doesn’t mean a consistent estimator has an expectation value that is equal to the true value for a finite amount of training data. It is possible to have a consistent estimator that is biased. This means the estimator, on average, will differ from the true value when we use a finite amount of training data. For a consistent estimator, if it is biased that bias will disappear as we continually increase the amount of training data.

As you might have guessed, the best algorithms produce estimators that are consistent and unbiased. Knowing if your estimator is biased and by how much is extremely useful. Again, we can assess bias using simulated data, and I’ll show how to do this in the next section when I show how to set up some simulation tests.

Efficiency check

So far, we have spoken about the expectation or average properties of an algorithm/estimator. But what about its variance. It is all very well telling me that across lots of different instances of training datasets my algorithm would, on average get the right answer, or near the right answer, under ideal conditions, but in the real world I have only one training dataset. Am I going to be lucky and my particular training data will give parameter estimates close to the average behaviour of the algorithm? I’ll never know. But what I can know is how variable the parameter estimates from my algorithm are. I can do this by calculating the variance of the parameter estimates over lots of training datasets. A small variance will tell me that my one real-world dataset is likely to have performance close to the mean behaviour of the algorithm. I may still be unlucky with my particular training data and the parameter estimates are a long way from the average estimates, but it is unlikely. However, a large variance tells me that parameter estimates obtained from a single training dataset will often be a long way from the average estimates.

How can I calculate this variance of parameter estimates over training datasets? Simple, get lots of different training datasets produced under identical controlled conditions. How could I do that? Yep, you guessed it. Simulation. With a simulation process coded up, we can easily generate multiple instances of training datasets of the same size and generated under identical conditions. Again, I’ll demonstrate this in the next section.

Sensitivity check – robustness to contamination

Our message about simulated data is that it allows you to test your algorithm under conditions that match the assumptions made by the algorithm, i.e. under ideal conditions. But you can use simulation to test how well your algorithm performs in non-ideal conditions. We can also introduce contamination into the simulated data, for example drawing some response variable values from a non-Gaussian distribution if our algorithm has assumed the response variable is purely Gaussian distributed. We can produce multiple simulated datsets with different percentages of contamination and so test how sensitive or robust our estimation algorithm is to the level of contamination, i.e. how sensitive it is to non-ideal data.

In the first few pages of the first chapter of his classic textbook on Robust Statistics, Peter Huber describes analysis of an experiment originally due to John Tukey. The analysis reveals that even having just 2% of “bad” datapoints being drawn from a different Gaussian distribution (with a 3-fold larger standard deviation) is enough to markedly change the properties and efficiency of common statistical estimators. And yet, defining “bad” data as being drawn from a larger variance Gaussian is wonderfully simplistic. Real-world data is so much nastier.

What form should the data contamination take? There are multiple ways in which data can become contaminated. There can be changes in statistical properties, like the simple example we used above, or drift in statistical properties such as a non-stationary mean or a non-stationary variance. But you can get more complicated errors creeping into your data. These typically take two forms,

- Human induced data contamination: These can be misspelling or mis-(en)coding errors that result from not using controlled and validated vocabularies for human data-entry tasks. You’ll recognize these sorts of errors when you see multiple different variants for the name of the same country, US county or UK city, say. You might think it is difficult to simulate such errors, but there are some excellent packages to do so – checkout the messy R package produced by Dr. Nicola Rennie that allows you to take a clean dataset and introduce these sorts of encoding errors into it. Spotting these errors can be as simple as plotting distributions of unique values in a table column, i.e. looking for unusual distributions. In R there are a number of packages to help you do this.

- Machine induced errors: These are errors that arise from the processing or transferring of data. These can be as simple as incorrect datetime stamps on rows in a database table, or can be as complex as repeating blocks of rows in a table. These errors are less about contamination and more about alteration. The common element here is that there is a pattern to how the data has become altered or modified and so spotting the errors involves visual inspection of the individual rows of the table, combined with plotting lagged or offset data values. The machine induced errors arise because of bugs in processing code, and these can be either coding errors, e.g. a typo in the code, or unintended behaviour, e.g. datetime processing code that hasn’t been designed properly to correctly handle daylight saving switchovers.

What kind of data contamination should I simulate? This is a “how long is a piece of string” kind of question. It very much depends on what aspect of your algorithm or implementation you want to test for robustness, and only you can know that. You may have to write some bespoke code to simulate the sorts of errors that arise in the processes you use or are exposed to. Broadly speaking, robustness of an estimator will be tested by changes in the statistical properties of the input data and these can be simulated by changes in the distributions of data due to data drift or human-induced contamination, whilst machine-induced errors imply you have some sort of deployed pipeline and so simulating machine corrupted data is best when you want to stress-test your end-to-end pipeline.

Runtime scaling

There are also checks that simulated data allows you to perform that aren’t necessarily directly connected to the accuracy or efficiency of the parameter estimates. Because we can produce as much simulated data as we want, we can easily test how long our estimation algorithm takes for different sized datasets. Similarly, we can also use simulated data to test the memory and storage requirements of the algorithm.

We can continue this theme. Because we can tune and tweak the generation of the simulated data, this can also allow us to generate data to test very specific scenarios – corner cases – for which we don’t have real test data. The ability to generate simulated data increases the test coverage we can perform.

What simulated data won’t give you

Identify model mis-specification

Using simulated data will tell you how well your model training algorithm performs on data that matches precisely the form of the model you have used. It won’t tell you if your model form is correct or appropriate for the real data you will ultimately apply it to. It won’t tell you if you’ve omitted an important feature or if you’ve put non-linearity into your model in an incorrect way. Getting the model form right can only come from i) domain expertise, ii) testing on real ground-truth data. Again, what this highlights is that we use simulated data to test the training process, not the model.

This can trip up even experience researchers. I recently saw a talk from an academic researcher who tested two different model forms using simulated data generated from one of the models. When the model form used to generate the data fitted the simulation data better, they confidently claimed that this model was better and more correct. Well, of course it was for this simulated data!

Accuracy of your model on real data

For simulated data we have the ground-truth values of the response variable so we can assess the prediction accuarcy, either on training data or on holdout test data. However, unless our simulation process produced very realistic data, including the various contamination processes, the test set accuracy on simulated data cannot be used as a precise measure of the predictive accuracy of the trained model on real unseen data.

How to simulate

When producing simulated data for testing an algorithm related to a model there are two things we need to generate – the features and the response. There are two ways we can approach this,

- Simulating the features and then simulating the response given the feature values we just produced.

- Simulate just the response value given some pre-existing feature values.

Of these, 2 sounds easier, but I will discuss 1 first as it leads us naturally into discussing where we might get pre-existing feature values from.

Simulating features and response

As we said above, in this approach we simulate the features first, and this allows us to construct the distribution of the response variable conditional on the features. We can then sample a value from that conditional distribution. Our basic recipe is

- Sample the feature values from a distribution.

- Use the sampled feature values and the model form to construct the distribution of the response variable conditional on the features.

- Sample the response variable from the conditional distribution constructed in 2.

How complex we want to make the feature distribution depends on how realistic we need our features to be and what aspect of the estimation/training algorithm we are wanting to test.

For real-world problems, it is unlikely that the features follow a Gaussian distribution. Take demand modelling, an area I have worked in a lot. The main feature we use is the price of the product whose demand we are trying to predict. Prices are definitely not Gaussian distributed. Retailers repeatedly switch between a regular and promotional price over a long period of time, so that we have a sample distribution of prices that is represented by two Dirac-delta functions. A more interesting price time series may introduce a few more price points, but it is still definitely not Gaussian. Similarly, real data has correlations between features.

When simulating a feature, we have to decide how important the real distribution is to the aspect of the estimation/training algorithm that we want to test. If we want to simulate with realistically distributed features. this can be problematic. We’ll return to this issue and real data later on, but for now we emphasize tha we can still test whether our estimator is consistent or assess its bias using features drawn from independent Gaussian distributions. So there are still useful tests of our estimation algorithm we can carry out. Let’s see how we can do that.

Linear model example

We’ll use a simple linear model that depends on three features,  . The response variable

. The response variable  is given by,

is given by,

From which you can see both the linear dependence on the features and that  contains Gaussian additive noise

contains Gaussian additive noise  .

.

Simulating data is now easy once we have the structure of our probabilistic model. Given a user-specified mean  and variance

and variance  we can easily sample a value for

we can easily sample a value for  from

from  . Similarly, given user-specified means

. Similarly, given user-specified means  and variances

and variances  , we can generate values for

, we can generate values for  and

and  . If we have user-specified values of

. If we have user-specified values of  we can then easily generate a value for

we can then easily generate a value for  by sampling from

by sampling from  , where

, where  is the variance of the additive noise that we want to add to our response variable. To simulate

is the variance of the additive noise that we want to add to our response variable. To simulate  datapoints we repeat that recipe

datapoints we repeat that recipe  times. Let’s apply that recipe to assess an estimator of the model parameters

times. Let’s apply that recipe to assess an estimator of the model parameters  . We’ll assess the standard Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator for a linear model.

. We’ll assess the standard Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator for a linear model.

Assessing the OLS Estimator for a linear model

Given a feature matrix  (the ith row of the matrix is the feature values for the ith observation) and vector

(the ith row of the matrix is the feature values for the ith observation) and vector  that represents the

that represents the  observations of the response variable, then the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator

observations of the response variable, then the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator  of the true model parameters

of the true model parameters  is given by the formula,

is given by the formula,

Note that the OLS estimator is a linear combination of the observations  , with a weight matrix

, with a weight matrix  . We’ll come back to this point in a moment.

. We’ll come back to this point in a moment.

What we want to know is how close is the estimate  to

to  . Is the OLS estimator in the Eq.1 above a biased estimator of

. Is the OLS estimator in the Eq.1 above a biased estimator of  , and is it a consistent estimator?

, and is it a consistent estimator?

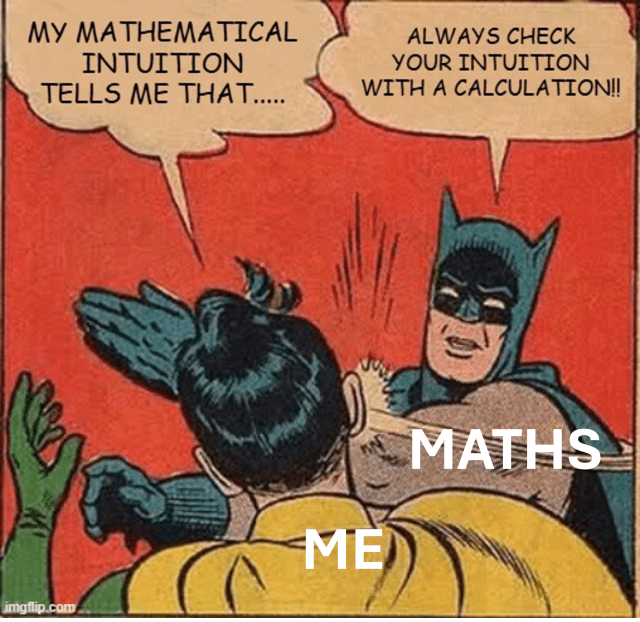

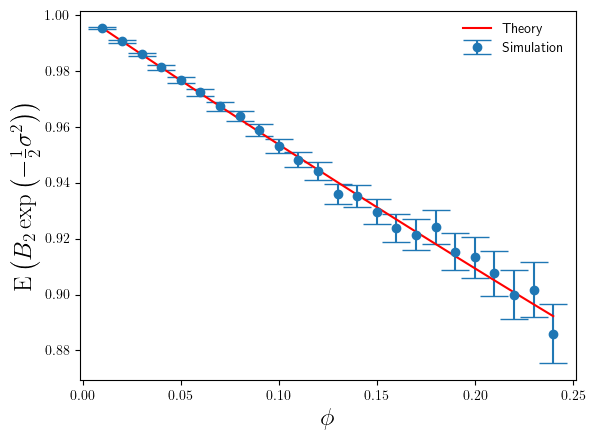

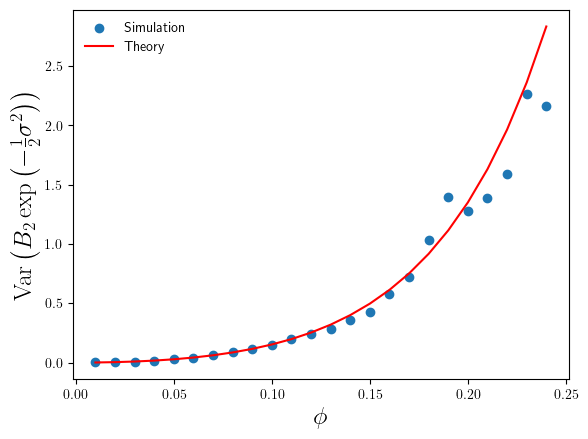

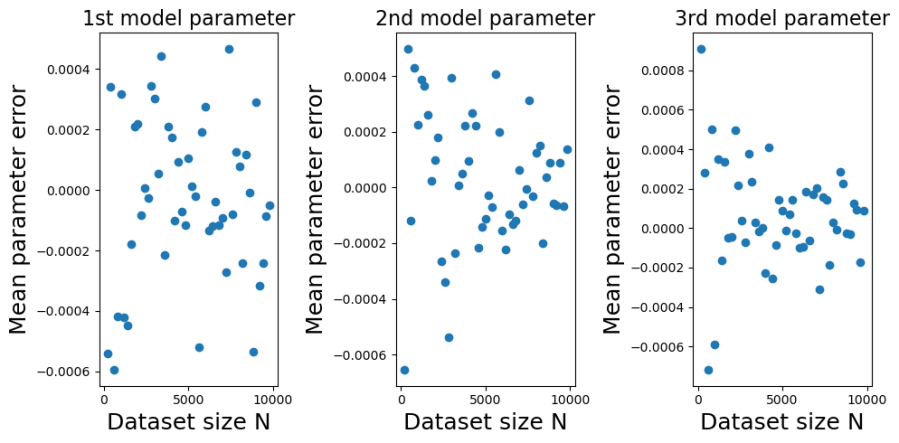

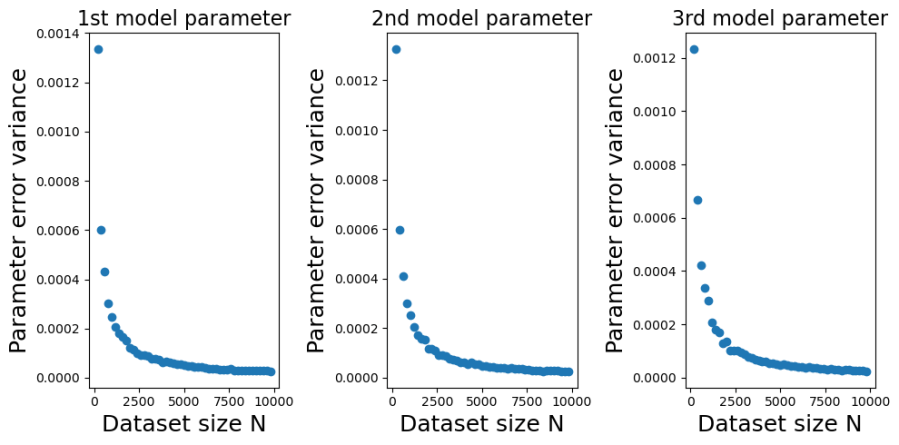

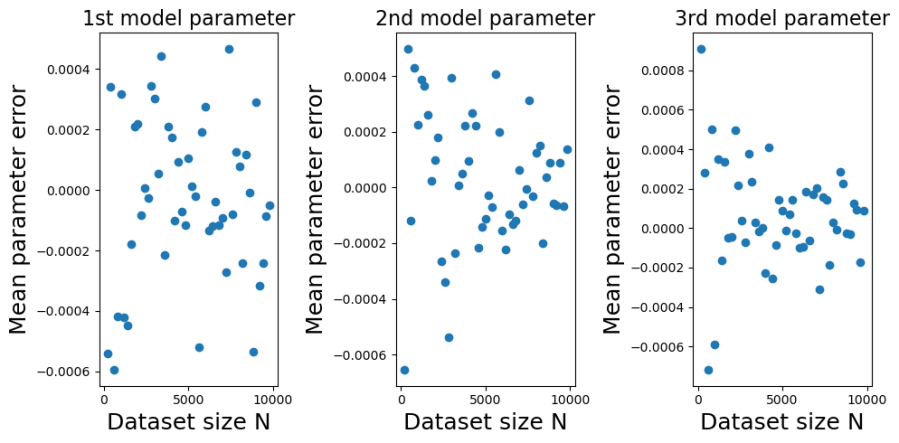

The plots below show the bias (mean error) for each of the model parameters, plotted against training dataset size  . I constructed the plots by initializing a true model parameter vector

. I constructed the plots by initializing a true model parameter vector  and then generating 1000 simulated training datasets for each of the different values of

and then generating 1000 simulated training datasets for each of the different values of  . For each simulated training dataset I computed the OLS parameter estimate

. For each simulated training dataset I computed the OLS parameter estimate  and then computed the parameter estimate errors

and then computed the parameter estimate errors  . From the errors I then calculated their sample means and variances (over the simulations) for each value of

. From the errors I then calculated their sample means and variances (over the simulations) for each value of  .

.

You can see from the plots that whilst the mean error fluctuates it doesn’t systematically change with  . Furthermore, it fluctuates around zero, suggesting that the OLS estimator is unbiased. And indeed it is. It is possible to mathematically show that the OLS estimator is unbiased at any finite value of

. Furthermore, it fluctuates around zero, suggesting that the OLS estimator is unbiased. And indeed it is. It is possible to mathematically show that the OLS estimator is unbiased at any finite value of  . The reason we get a non-zero value in this case is because we have estimated

. The reason we get a non-zero value in this case is because we have estimated  using a sample average taken over 1000 simulated datasets. If we had used a larger number of simulated datasets we would have got even smaller sample average parameter errors.

using a sample average taken over 1000 simulated datasets. If we had used a larger number of simulated datasets we would have got even smaller sample average parameter errors.

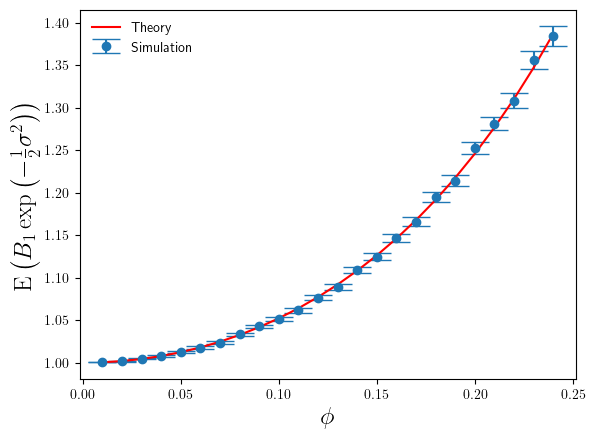

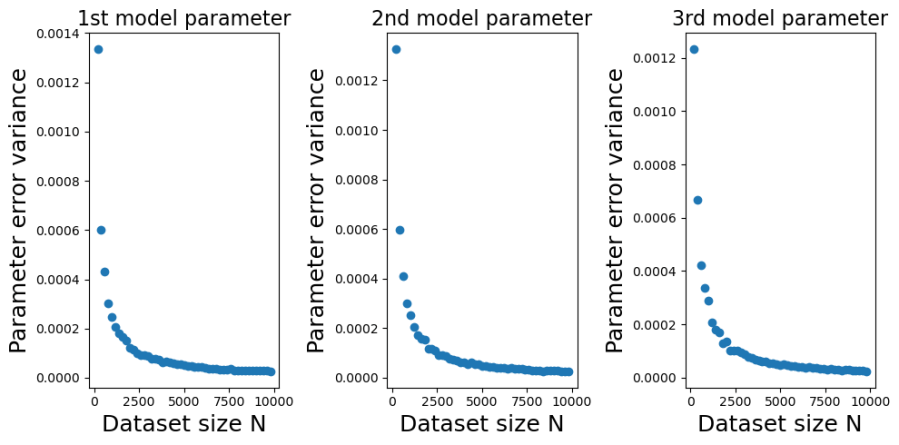

Contrast this behaviour with how the variances of the parameter estimate errors change with  in the plots below.

in the plots below.

The decrease, with  , in the variance of

, in the variance of  is marked. In fact, in looks like a power-law decrease, so I have plotted the same data on a log-scale below,

is marked. In fact, in looks like a power-law decrease, so I have plotted the same data on a log-scale below,

We can see from those log-log plots that the variances of  decrease as

decrease as  . That implies that as we use larger and larger training sets any single instance of

. That implies that as we use larger and larger training sets any single instance of  will get closer and closer to

will get closer and closer to  . At large

. At large  we have a low probability of being unlucky and our particular training set giving a poor estimate of

we have a low probability of being unlucky and our particular training set giving a poor estimate of  .

.

How efficient is the OLS estimator in Eq.1? Is the rate at which  decreases with

decreases with  good or bad? It turns out that the OLS estimator in Eq.1 is the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE). For an unbiased estimator of

good or bad? It turns out that the OLS estimator in Eq.1 is the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE). For an unbiased estimator of  that is constructed as a linear combination of the observations

that is constructed as a linear combination of the observations  , you cannot do better than the OLS estimator in Eq. 1.

, you cannot do better than the OLS estimator in Eq. 1.

All the code for the linear model example is available in the Jupyter notebook NeedForSimulation_Blogpost.ipynb in the GitHub repository https://github.com/dchoyle/simulation_blogpost.

A linear model is relatively simple structure but the example was a good demonstration of the power of simulated data. Next, we’ll use a more complex model architecture and build a feed-forward neural network.

Neural network example

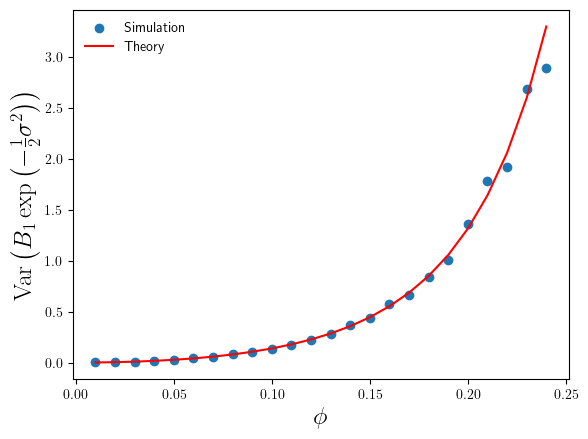

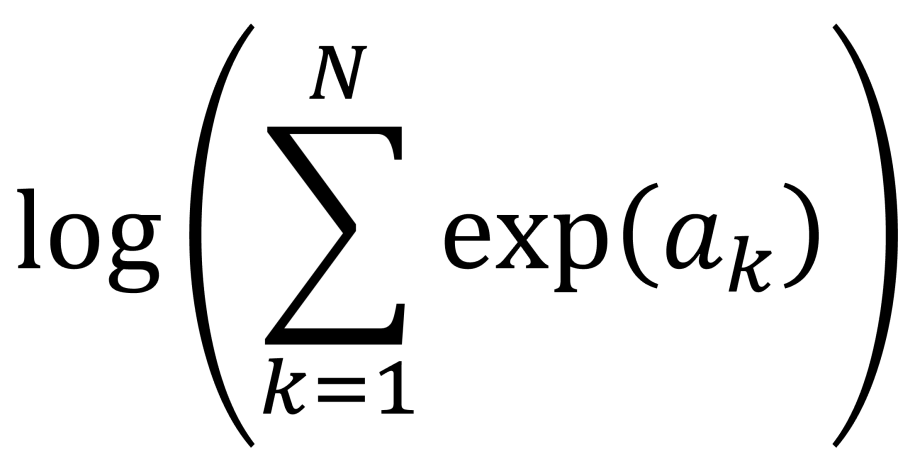

Our simulated neural network output has the form,

Again, we’ll use zero-mean Gaussian additive noise,  .

.

The function  represents our neural network function, with

represents our neural network function, with  being the vector of input features and

being the vector of input features and  being a vector holding all the network parameters. For this demo, I’m going to use a 3 input-node, 2 hidden-layer feed-forward network, with 10 nodes in each of the hidden layers. The output layer consists of a single node, representing the variable

being a vector holding all the network parameters. For this demo, I’m going to use a 3 input-node, 2 hidden-layer feed-forward network, with 10 nodes in each of the hidden layers. The output layer consists of a single node, representing the variable  . For the non-linear transfer (activation) functions I’m going to use

. For the non-linear transfer (activation) functions I’m going to use  functions. So, schematically, my networks looks like the figure below,

functions. So, schematically, my networks looks like the figure below,

I’m going to use a teacher network of the form above to generate simulated data, which I’ll then use to train a student network of the same form. What I want to test is, does my training process produce a trained student network whose predictions on a test set get more and more accurate as I increase the amount of training data? If not, I have a problem. If my training process doesn’t produce accurate trained networks on ideal data, the training process isn’t going to produce accurate networks when using real data. I’m less interested in comparing trained student network parameters to the teacher network parameters as, a) there are a lot of them to compare, b) since the output of a network is invariant to within-layer permutation of the hidden layer node labels and connections, defining a one-to-one comparison of network parameters is not straight forward here. Node 1 in the first hidden layer of the student isn’t necessarily equivalent to node 1 in the first hidden layer of the teacher network, and so on.

The details of how I’ve coded up the networks and set-up the evaluation are lengthy, so I’ll just show the final result here. All the details can be found in the Jupyter notebook NeedForSimulation_Blogpost.ipynb in the freely accesible github repository.

Below in left-hand plot I’ve plotted the average Mean Square Error (MSE) made by the trained student network on the test-sets. I’ve plotted the average MSE against the training dataset size. The average MSE is the average over the simulations of that training set size. For comparison, I have also calculated the average test-set MSE of the teacher network. Since the test-set data contains additive Gaussian noise, the teacher network won’t make perfect predictions on the test-set data even though the teacher network generated the systematic part of the test-set response values. The average test-set MSE of the teacher network provides a benchmark or baseline against which we can asses the trained student network. We have a ready intuition about the relative test-set MSE value. We expect the relative test-set MSE to be significantly above 1 at small values of  , as the student network struggles to learn the teacher network output. As the amount of training data

, as the student network struggles to learn the teacher network output. As the amount of training data  increases we expect the relative test-set MSE value to approach 1 from above. The average relative test-set error is plotted in the right-hand plot below.

increases we expect the relative test-set MSE value to approach 1 from above. The average relative test-set error is plotted in the right-hand plot below.

We can see from both plots above that the prediction accuracy of a trained student network typically decreases with increasing amount of training data. My network training process has passed this basic test. The test was quick to set up and gives me confidence I can run my code over real data.

Sampling features from more realistic distributions

In our previous examples we have used independent features, sampled from simple but naive distributions, to test the convergence properties of an estimator. But what happens if you want to assess the quantitative performance of an estimator for more realistic feature patterns? Well, we use more realistic feature patterns. This is a variant of our previous basic recipe, but where we have access to a real dataset. The modified recipe is,

- Sample an observation from the real dataset and keep the features.

- Use the sampled feature values and the model form to construct the distribution of the response variable conditional on the features.

- Sample the response variable from the conditional distribution constructed in 2.

This seems like a small modification of the recipe. However, it does have some big implications. We can’t generate simulated datasets of arbitrarily large size as we are limited by the size of the real dataset. We can obviously generate simulated datasets of smaller size than the real data, but this can make testing of the convergence properties of an estimator difficult.

That said, this is one of my faviourite approaches. Often, steps 2 and 3 are easy to implement. You’ll have a function for the conditional mean of the response variable already coded up for prediction purpose, so it is just a question of pushing some feature values through that code. I find the overhead of writing extra functions to simulate realistic looking feature values is significant, both in terms of time and thinking about what ‘realistic’ should look like. The recipe above gets round this easily. Simply pick a row from your existing real dataset at random and there you go, you have some realistic feature values. As before, the recipe allows me to then generate response values with known ground-truth parameters values. So overall I can compare parameter estimates to ground truth parameter values on realistic feature values, allowing me to check that my estimation algorithm is at least semi-accurate on realistic feature values. You can also choose in step 1 of the recipe, whether you want to sample a row of feature values with or without replacement.

Simulating the response only

You could argue that simulating response values with feature values sampled from an existing real dataset is an example of just simulating the response. After all, only the response value is computer generated. I still tend to think of it as simulating the features because, i) I am still sampling the features from a distribution function, the empirical distribution function in this case, and ii) I have broken some of the link between the features and the response in the real data because I have sampled the features values separately. However, sometimes we want to keep as much as of the links between features and response values in the real data as possible. We can do this by only making additions to the real data. By necessity this means only adding to the response value. This may sound very restrictive, but in fact there are many situations where this is precisely the kind of data we need to test an estimation algorithm. For example, changepoint detection or unconditional A/B testing. In these situations we take the real data, identify the split point where we want to increase the response value (the changepoint or the A/B grouping) and simply increase the response. Hey presto, we have realistic data with a guaranteed increase in the response variable at a know location. By changing the level of increase in the response variable we can use this approach to assess the statistical power of the changepoint or A/B test algorithm.

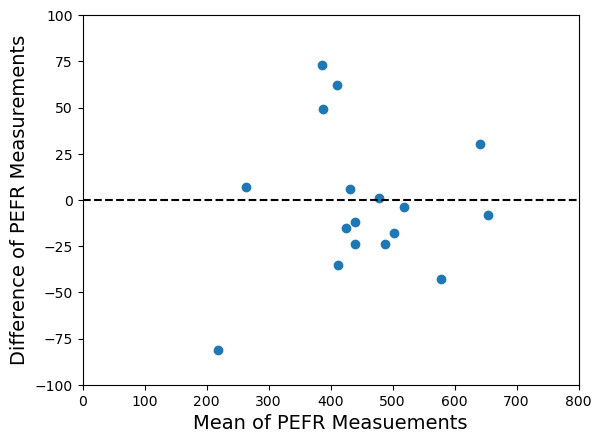

The plots below show an example of introducing a simple shift in level at timepoint 53 into a real dataset. We have only shown the process as a simple schematic, but coding it up yourself is only a matter of a line or two of code, so I haven’t given any code details.

In the above example I simply increased the response variable, by the same amount (8.285 in this case), at and after timepoint 53. If instead, you only want to increase the average value of the response variable, it is a simple modification of the process to include some additional zero-mean noise after the changepoint location.

Conclusions

Simulated data is extremely useful. It can give you lots of insight into the performance of your training/estimation algorithm (including bug detection). Its main advantages are it is,

- Easy to produce in large volumes.

- Can be produced in a user-controlled way.

- Gives you ground-truth values.

- Gives you a way to assess the performance of your training algorithm when you have no real ground-truth data.

- Stops you releasing a poor untested training algorithm into production.

If you don’t want to sign an absolutely useless striker for your data science model team, test with simulated data at the very minimum.

Footnotes

- Harry Redknapp is a former English Premier League football manager. Whilst Redknapp was manager of Tottenham Hotspur he had a reputation of being willing to sign players on the flimiest of evidence of footballing skills. At a time when there was a large influx of overseas players into the Premier league, due to their reputation for superior technical football skills, it was joked that he would sign a player simply because of how their name sounded and without any checks on the player at all.

- The term generative model preceeds its useage in Generative AI. Broadly speaking, a generative model is a machine learning model that learns the underlying probability distribution of the data and can generate new, similar data instances. The useage of the term was popular around the early 2000’s, particularly when discussing different forms of classifiers, which were described as either being generative or discriminative.

© 2025 David Hoyle. All Rights Reserved