Introduction

TL;DR: There are tests on models you can do even before you have done any training of the model. These are tests of the model form, and are more mathematical in nature. These tests stop you from putting a model with a flawed mathematical form into production.

My last blogpost was on using simulation data to test a model. I was asked if there are other tests I do for models, to which I replied, “other than the obvious, it depends on the model and the circumstances”. Then it occurred to me that “the obvious” tests might not be so obvious, so I should explain them here.

Personally, I broadly break down model tests into two categories:

- Tests on a model before training/estimation of the model parameters.

- Tests on a model after training/estimation of the model parameters.

The first category (pre-training) are typically tests on model form – does the model make sense, does the model include features in a sensible way. These are tests that get omitted most often and the majority of Data Scientists don’t have in their toolkit. However, these are tests that will spot the big costly problems before the model makes it into production.

The second category of tests (post-training) are typically tests on the numerical values of the model parameters and various goodness-of-fit measures. These are the tests that most Data Scientists will know about and will use regularly. Because of this I’m not going to go into details of any tests in this second category. What I want to focus on is tests in the first category, as this is where I think there is a gap in most Data Scientists’ toolkit.

The tests in the first category are largely mathematical, so I’m not going to give code examples. Instead, I ‘m just going to give a short description of each type of test and what it tries to achieve. Let’s start.

Pre-training tests of model form

Asymptotic behaviour tests:

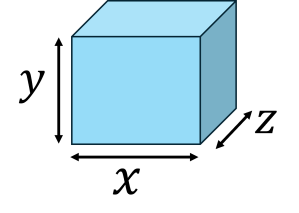

One of the easiest ways to test a model form is to look at its output in circumstances which are easy to understand. In a model with many features and interacting parts this is best done by seeing what happens when you make one of the variables or parameters as large as possible (or as small as possible). In these circumstances the other variables will often become irrelevant and so the behaviour of the model is easier to spot. For example, in a demand model that predicts how much of a grocery product you’re going to sell, does putting up the price to infinity cause the predicted sales volume to drop to zero? If not, you’ve got a problem with your model.

Asymptotic behaviour tests are not limited to scenarios in which variables/parameters become very large or very small. In some cases the appropriate asymptotic scenario might be a parameter approaching a finite value at which a marked change in behaviour is expected. It should be clear that identifying asymptotic scenarios for which we can easily predict what should happen can require some domain knowledge. If you aren’t confident of your understanding of the application domain, then a good start is to make variables/parameters very large and/or very small one at a time and see if the resulting behaviour makes sense.

Typically, working out the behaviour of your model form in some asymptotic limit can be done simply by visual inspection of the mathematical form of your model, or with a few lines of pen-and-paper algebra. This gives us the leading order asymptotic behaviour. With a bit more pen-and-paper work we can also work out a formula for the next-to-leading order term in the asymptotic expansion of the model output. The next-to-leading order term tells us how quickly the model output approaches its asymptotic value – does it increase to the asymptotic value as we increase the variable, or does it decrease to the asymptotic value? We can also see which other variables and parameters affect the rate of this approach to the asymptotic value, again allowing us to identify potential flaws in the model form.

The asymptotic expansion approach to testing a model form can be continued to even higher orders, although I rarely do so. Constructing asymptotic expansions requires some experience with specific analysis techniques, e.g. saddle-point expansions. So I would recommend the following approach,

- Always do the asymptotic limit (leading order term) test(s) as this is easy and usually requires minimal pen-and-paper work.

- Only derive the next-to-leading order behaviour if you have experience with the right mathematical techniques. Don’t sweat if you don’t have the skills/experience to do this as you will still get a huge amount of insight from just doing 1.

Stress tests/Breakdown tests:

These are similar in spirit to the asymptotic analysis tests. Your looking to see if there are any scenarios in which the model breaks down. And by “break down”, I mean it gives a non-sensical answer such as predicting a negative value for a quantity that in real life can only be positive. How a model breaks down can be informative. For example, does the scenario in which the model breaks down clearly reflect an obvious limitation of the model assumptions, in which case breakdown is entirely expected and nothing to worry about. The breakdown is telling you what you already know, that in this scenario the assumptions don’t hold or are inappropriate and so we expect the model to be inaccurate or not work at all. If the breakdown scenario doesn’t reflect known weaknesses of the model assumptions you’ve either uncovered a flaw in the mathematical form of your model, which you can now fix, or you’ve uncovered an extra hidden assumption you didn’t know about. Either way, you’ve made progress.

Recover known behaviours:

Another test that has similarities to the asymptotic analysis and the stress tests. For example, your model may be a generalization of a more specialized model. It may contain extra parameters that capture non-linear effects. If we set those extra parameters to zero in the model or in any downstream mathematical analysis we have performed, then we would expect to get the same behaviour as the purely linear model. Is this what happens? If not, you’ve got a problem with your model or the downstream analysis. Again this is using known expected behaviour of a nested sub-case as a check on the general model.

Coefficients before fitting:

Your probably familiar with the idea of checking the parameters of a model after fitting, to check that those parameter values make sense. Here, I’m talking about models with small numbers of features and hence parameters, which also have some easy interpretation. Because we can interpret the parameters we can probably come up with what we think are reasonable ball-park values for them even before training the model. This gives us, i) a check on the final fitted parameter values, and ii) a check on what scale of output we think is reasonable from the model. We can then compare what we think should be the scale of the model output against what is needed to explain the response data. If there is an order of magnitude or more mis-match then we have a problem. Our model will either be incapable of explaining the training data in its current mathematical form, or one or more of the parameters is going to have an exceptional value. Either way, it is probably wise to look at the mathematical form of your model again.

Dimensional analysis:

In high school you may have encountered dimensional analysis in physics lessons. There you checked that the left-hand and right-hand sides of a formula were consistent when expressed in dimensions of Mass (M), Length (L), and Time (T). However, we can extend the idea to any sets of dimensions. If the right-hand side of a formula consists of clicks divided by spend, and so has units of , then so must the left-hand side. Similarly, arguments to transcendental functions such as exp or sin and cos must be dimensionless. These checks are a quick and easy way to spot if a formula is inadvertently missing a dimensionful factor.

Conclusion:

These tests of the mathematical form of a model ensure that a model is robust and its output is sensible when used in scenarios outside of its training data. And let’s be realistic here; in commercial Data Science all models get used beyond the scope for which they are technically valid. Not having a robust and sensible mathematical form for your model means you run the risk of it outputting garbage.

© 2025 David Hoyle. All Rights Reserved