Summary

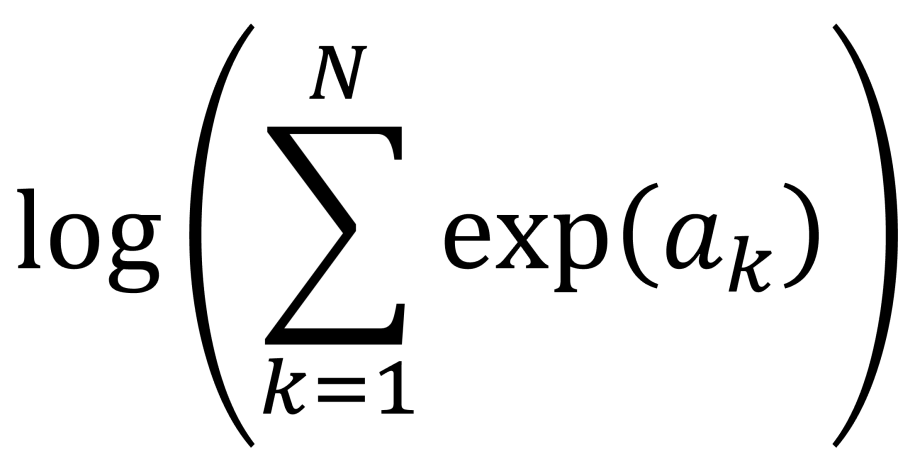

- Summing up many probabilities that are on very different scales often involves calculation of quantities of the form

. This calculation is called log-sum-exp.

- Calcuating log-sum-exp the naive way can lead to numerical instabilities. The solution to this numerical problem is the “log-sum-exp” trick.

- The scipy.special.logsumexp function provides a very useful implementation of the log-sum-exp trick.

- The log-sum-exp function also has uses in machine learning, as it is a smooth, differentiable approximation to the

function.

Introduction

This is the second in my series of Data Science Notes series. The first on Bland-Altman plots can be found here. This post is on a very simple numerical trick that ensures accuracy when adding lots of probability contributions together. The trick is so simple that implementations of it exist in standard Python packages, so you only need to call the appropriate function. However, you still need to understand why you can’t just naively code-up the calculation yourself, and why you need to use the numerical trick. As with the Bland-Altman plots, this is something I’ve had to explain to another Data Scientist in the last year.

The log-sum-exp trick

Sometimes you’ll need to calculate a sum of the form, , where you have values for the

. Really? Will you? Yes, it will probably be calculating a log-likelihood, or a contribution to a log-likelihood, so the actual calculation you want to do is of the form,

These sorts of calculations arise where you have log-likelihood or log-probability values for individual parts of an overall likelihood calculation. If you come from a physics calculation you’ll also recognise the expression above as the calculation of a log-partition function.

So what we need to do is exponentiate the values, sum them, and then take the log at the end. Hence the expression “log-sum-exp”. But why a blogpost on “log-sum-exp”? Surely, it’s an easy calculation. It’s just np.log(np.sum(np.exp(a))) , right ? Not quite.

It depends on the relative values of the . Do the naïve calculation np.log(np.sum(np.exp(a))) and it can be horribly inaccurate. Why? Because of overflow and underflow errors.

If we have two values and

and

is much bigger than

, when we add

to

we are using floating point arithmetic to try and add a very large number to a much smaller number. Most likely we will get an overflow error. If would be much better if we’d started with

and try to add

to it. In fact, we could pre-compute

, which would be very negative and from this we could easily infer that adding

to

would make very little difference. In fact, we could just approximate

by

.

But how negative does have to be before we ignore the addition of

? We can set some pre-specified threshold, chosen to avoid overflow or underflow errors. From this, we can see how to construct a little Python function that takes an array of values

and computes an accurate approximation to

without encountering underflow or overflow errors.

In fact we can go further and approximate the whole sum by first of all identifying the maximum value in an array . Let’s say, without loss of generality, the maximum value is

. We could ensure this by first sorting the array, but it isn’t necessary actually do this to get the log-sum-exp trick to work. We can then subtract

from all the other values of the array, and we get the result,

The values are all negative for

, so we can easily approximate the logarithm on the right-hand side of the equation by a suitable expansion of

. This is the “log-sum-exp” trick.

The great news is that this “log-sum-exp” calculation is so common in different scientific fields that there are already Python functions written to do this for us. There is a very convenient “log-sum-exp” function in the SciPy package, which I’ll demonstrate in a moment.

The log-sum-exp function

The sharp-eyed amongst you may have noticed that the last formula above gives us a way of providing upper and lower bounds for the function. We can simply re-arrange the last equation to get,

The logarithm calculation on the right-hand side of the inequality above is what we call the log-sum-exp function (lse for short). So we have,

This gives us an upper bound for the ${\rm max}$ function. Since , it is also relatively easy to show that,

and so we have have a lower bound for the function. So the log-sum-exp function allows us to compute lower and upper bounds for the maximum of an array of real values, and it can provide an approximation of the maximum function. The advantage is that the log-sum-exp function is smooth and differentiable. In contrast, the maximum function itself is not smooth nor differentiable everywhere, and so is less convenient to work with mathematically. For this reason the log-sum-exp is often called the “real-soft-max” function because it is a “soft” version of the maximum function. It is often used in machine learning settings to replace a maximum calculation.

Calculating log-sum-exp in Python

So how do we calculate the log-sum-exp function in Python. As I said, we can use the SciPy implementation which is in scipy.special. All we need to do is pass an array-like set of values . I’ve given a simple example below,

# import the packages and functions we needimport numpy as npfrom scipy.special import logsumexp# create the array of a_k values a = np.array([70.0, 68.9, 20.3, 72.9, 40.0])# Calculate log-sum-exp using the scipy function lse = logsumexp(a)# look at the resultprint(lse)This will give the result 72.9707742189605

The example above and several more can be found in the Jupyter notebook DataScienceNotes2_LogSumExp.ipynb in the GitHub repository https://github.com/dchoyle/datascience_notes

The great thing about the SciPy implementation of log-sum-exp is that it allows us to include signed scale factors, i.e. we can compute,

where the values are allowed to be negative. This means, that when we are using the SciPy log-sum-exp function to perform the log-sum-exp trick, we can actually use it to calculate numerically stable estimates of sums of the form,

.

Here’a small code snippet illustrating the use of the scipy.special.logsumexp with signed contributions,

# Create the array of the a_k valuesa = np.array([10.0, 9.99999, 1.2])b = np.array([1.0, -1.0, 1.0])# Use the scipy.special log-sum-exp functionlse = logsumexp(a=a, b=b)# Look at the resultprint(lse)This will give the result 1.2642342014146895.

If you look at the output of the example above you’ll see that the final result is much closer to the value of the last array element . This is because the first two contributions,

and

almost cancel each other out because the contribution

is pre-fixed by a factor of -1. What we get left with is something close to

.

There is also a small subtlety in using the SciPy logsumexp function with signed contributions. If the substraction of some terms had led to an overall negative result, scipy.special.logsumexp will rerturn NaN as the result. In order to get it to always return a result for us, we have to tell it to return the sign of the final summation as well, by setting the return_sign argument of the function to True. Again, you can find the code example above and others in the notebook DataScienceNotes2_LogSumExp.ipynb in the GitHub repository https://github.com/dchoyle/datascience_notes.

When you are having to combine lots of different probabilities, that are on very different scales, and you need to subtract some of them and add others, the SciPy log-sum-exp function is very very useful.

© 2026 David Hoyle. All Rights Reserved