Unsurprisingly, given my day job, I ended up reading several books about forecasting in 2023. On reflection, what was more surprising to me was the variety. The four books I have read (admittedly, not all of them cover-to-cover) span the range from a history of general technology forecasting, the current state of the art and near future of forecasting methods in business, right through to the specific topic of intermittent demand modelling. Hence the title of this blogpost, “The past, the future, and the infrequent”, which is a play on the spaghetti western “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly”. It also gives me an opportunity to play around with my Stability AI prompting skills to create the headline image above.

The Books

Since I really enjoyed all four of the books, I thought I’d post a short summary and review of each of them. The four books are,

What the books are about

- (Top left) – “A History of the Future: Prophets of Progress from H.G. Wells to Isaac Asimov”, by Peter J. Bowler. Published by Cambridge University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1-316-60262-1.

- This is not really a book about forecasting in the way that a Data Scientist would use the word “forecasting”. It is a book about the history of “futurology” – the practice of making predictions about what the world and society will be like in the future, how it will be shaped by technological innovations, and what new technological innovations might emerge. The book reviews the successes and failures of futurologists from the 20th century and what themes were present in those predictions and forecasts. What is interesting is how the forecasts were often shaped by the background and training of the forecaster – forecasts from people with a scientific training or background tended to be more optimistic than those from people with more arts or literary backgrounds. I did read this book from end-to-end.

- (Top right) – “Histories of the Future: Milestones in the last 100 years of business forecasting”, by Jonathon P. Karelse. Published by Forbes Books, 2022. ISBN= 978-1-955884-26-6.

- This is another book about the history of forecasting. As one of the reviewers, Professor Spyros Makridakis, says on the inside cover of the book, this is not a “how to” guide. However, each chapter of the book does focus on a prominent forecasting method that is used widely in business settings – Chapter 3 covers exponential smoothing, Chapter 5 covers Holt-Winters, Chapter 7 covers Delphi methods – but each method is introduced and discussed from the historical perspective of how the method arose and was used in genuine operational business settings. Consequently, the methods discussed do tend to be the simpler but more robust methods that have stood the test of time of being used in genuine real-world business settings, although the final chapter does discuss AI and ML forecasting methods. This is another book I did read end-to-end.

- (Bottom left) – “Demand Forecasting for Executives and Professionals”, by Stephan Kolassa, Bahman Rostami-Tabar, and Enno Siemsen. Published by CRC Press, 2023. ISBN=978-1-032-50772-9.

- This is a technical book. However, it has relatively few equations and those equations that it does contain are relatively simple and understandable by anyone with high-school maths, or who has taken a maths module in the first year of a Bachelor’s degree. That is deliberate. As the book says in the preface it “is a high-level introduction to demand forecasting. It will, by itself, not turn you into a forecaster.” The book is aimed at executives and IT professionals whose responsibilities include managing forecasting systems. It is designed to give an overview of the forecasting process as a whole. My only criticism is that, even given the focus on delivering a high-level overview of forecasting and how it should be used and implemented as a process, the topics covered are still ambitious. My experience is that senior managers, even technical ones, won’t have the time to read about ARIMA modelling even at the level it is covered in this book. That said, the breadth of the book (in under 250 pages) and its focus on forecasting as a process is what I like about it. It emphasizes the human element of forecasting via the interaction and involvement that a forecaster or consumer of a forecast has with the forecasting process. These are things you won’t get from a technical book on statistical forecasting methods and that you usually only learn the hard way in practice. If I had an executive or senior IT manager who did want to learn more about forecasting and I could recommend only one book to them, this would be it. As a Data Scientist this is still an interesting book. There is still material I have read and learnt from, but as a Data Scientist it has been a book I have only dipped in and out of.

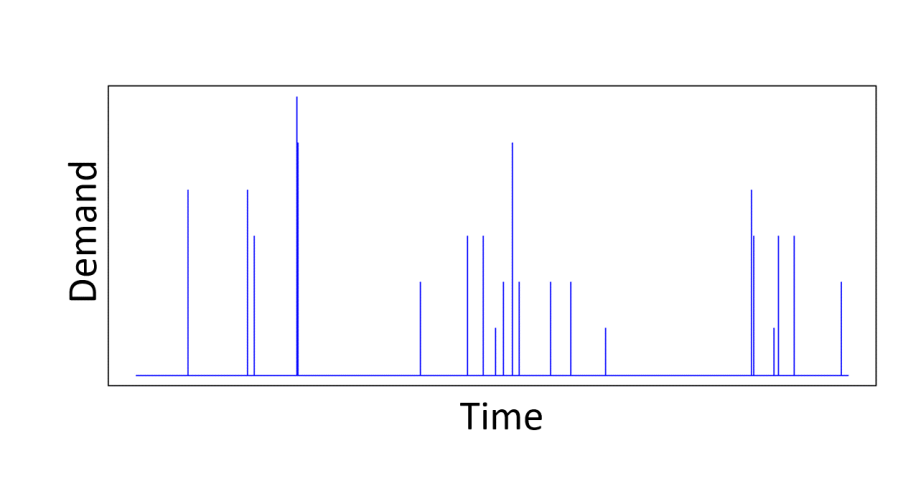

- (Bottom right) – “Intermittent Demand Forecasting: Context, Methods and Application”, by John E. Boylan and Aris A. Syntetos. Published by Wiley 2021. ISBN=978-119-97608-0.

- Professor John Boylan passed away in July 2023. I was fortunate enough to attend a webinar in February 2023 that John Boylan gave about intermittent demand forecasting. I learnt a lot from the webinar. It also meant that I was already familiar with a lot of the context on reading the book, making reading the book more enjoyable. In fact, the seminar was where I first came across the book. The book is technical. It is the most technical and focused of the four books reviewed here. It is a book on the best statistical models and methodologies for forecasting intermittent demand, particularly for inventory-management applications. It is an in-depth “how-to” book. As far as I am aware this book is the most up-to-date, comprehensive, and authoritative book on intermittent demand forecasting there is. Since it is a technical book, it is a book I have dipped in and out of, rather than read end-to-end.

I can genuinely recommend all four books. The first two books I enjoyed the most, because I find that personally, reading about the history of how scientific methods and algorithms arise gives extra insight into the nuances of the methods and when and where they work best. The second two books are more “how-to” books – you can find similar material on the internet, in various blog articles and academic papers etc. However, it is always great to have methods explained by practitioners who are also experts in those methods.

The content of the last three books would be more recognizable by your typical working Data Scientist. The first book is more of a book for historians, but I enjoyed it because the subject matter it addressed was in an area/domain relevant to me, that of long-range forecasting.

© 2024 David Hoyle. All Rights Reserved